Chapter 11

Speakers and Cabs

Warning: Impedance must be matched between amp and cab, or you can damage both (see below).

Speakers and cabs contribute to your tone as much as the amp and guitar do. If you go directly to an amp, you could split it all into 1/3rds in tonal contribution (pickup, amp, and cab), but speaker cabs contribute much more than amp dialings or pickups. Unlike amps, there is a short list of usual suspects regarding what guitarists use for speakers. You can throw money down on the speaker being a V30 for metal, Greenback for rock, and Jensen for country. If it isn’t one of those, then it is something trying to copy them. If it isn’t a copy, you can start to find some familiar outsiders that make appearances, but there is much more out there.

To find this out, own a modeler or a cab sim, keep everything about the rig the same, but switch around the cabs/speakers. The variety is so astonishing that you can hardly imagine how anyone could own even a fraction of them all to try them out for just one amp! This is why there is a list of usual suspects for speakers because many guitarists are sticking to what the amp maker recommends to pair with it. Tried and trusted works here.

Combos are engineered so that the actual combination itself creates a specific type of sound. The amp will be close to the speaker, and often, nothing separates them more than the metal of the chases. Tubes may even be hanging right behind where the speaker goes as the chassis is upside down compared to the head version (if there is a head version). It is not the case that a single wooden baffle here or there drastically changes tone. Still, the sum of all these components produces emergent properties, one of which is the internal resonance that impacts the speaker’s tone.

A combo is engineered to be fine-tuned to tone with that resonance behavior interacting with a specific speaker in the cab. That is why some well-known popular combos aren’t available as head and cab combinations except maybe as some vintage gear. Good examples of this are various Fender combos and Vox combos. Also, they are another excellent example of where people stick to the amp maker’s speaker recommendations. Again, the usual suspects, this time for combos.

One way to ensure that a guitarist gets a matched set is to produce combos. The manufacturer would already have the amp and speaker together in one case. It is crucial to understand that combos, particularly well-established vintage ones, are designed with one system in mind with all components and no modifications to sound as intended—especially with custom combos.

Fender ’57 Custom Deluxe Tweed. A 1×12 combo. This combo is well known for forming a single system of sound. You would lose some tonal characteristics if you changed anything like the wood, panels, or speaker.

There is no immediate reason not to go with the matching cab unless you know the speakers are budget versions of a better option. You may notice that the makers of that amp and matching cab may also offer other cabs with those better speakers. You will likely have to pay more, but it is better now than down the line. This is for budget versions compared to the standard version if the brand offers it. The other reason not to go with the matching cab is that you copy some artist’s tone and go for what cab they use.

Getting a matching set helps the guitarist achieve how the engineers designed the stack to sound, so getting the paired cabinet will help you to get what the designers intended. You can know that any missing tonal components are not due to bad gear combination choices for that tone. It is a minor point but helpful for beginners (meaning anyone new to that amp) to distinguish how speakers can change things dramatically. If you swap out the cabinet for another, you enter into experimentation, and things might not go so well. How do you know how the amp was intended to sound if you don’t have the intended cab? Cab sims can help out here a bit to discern differences.

Two different cabinets can have the same speakers inside but sound very different. That is because resonance within the cabinet design influences the speakers. Think of closed-back and open-back cabinets with the same design, speaker configuration, and models. They sound different. So, design matters. Yes, they can sometimes be close, but it depends on what gear is being compared. It’s on a case-by-case basis.

So why so many choices if so similar in the mid-range, you might think? Enough for the speaker market to be quite lively. Various speaker models have different frequency responses to meet the demands of each music genre. This means you can specialize and venture into speakers that might lean more towards the tone you want than the usual suspects. You will find signature speakers from artists with their voicing.

Celestion EVH G12. It’s similar to a standard G12 but voiced slightly more towards Eddie Van Halen’s tone.

Instead of changing speakers, using a different cab is an alternative method. It requires more space but less work because you don’t have to swap out speakers. Marshall heads on Mesa Boogie cabs. Diezel heads on Marshall cabs. Mesa Boogie heads on Orange cabs. These happen because it works for some tones. Simple as that. A tone was sought after, and switching out an amp or cab got the guitarist there. You will see these odd pairings on stage, often at festivals. However, it is essential to understand that their experimentation is not yours. That has to be done for yourself and only after you have some experience with what matches first. Again, modeling gear saves you a lot of wasted money by experimenting with different cabs and speakers.

Guitar cab and combo speakers come in two main sizes, 12” or 10”, with 12” being the most popular, but 10” are often found in combos. There is a third 8” size for even smaller combos, but not so common. All of them are found inside guitar cabinets and combos. They can be purchased separately. There are also some vintage speakers bigger than 12″, but for the most part the 12″ and the 10″ are the most common you will find and also hear.

Cabinets are made with doubling the number of speakers inside in mind. A 1×12 cabinet has one 12” speaker inside; the next step is a 2×12. Doubling that again, we get a 4×12. That’s covering all modern cab sizes there. Doubling that again, we get 8×12, but these are not so common because they are just enormous, modern custom, or some old vintage stuff around you see popping up mainly for the fun of it or the ego of it. Still, big ego and tones will combine, which is done with a full stack of two 4x12s stacked with the amp head, the cherry on top.

A wall of sound is when you have a row of full stacks, but it can also mean many combos if that’s the style. You will see walls of sound at some major festivals. The wall stays throughout because of how long it takes to set up.

Let’s get down to the big question. Do you need a full stack? The answer is likely going to be no. You rarely find them in studios. They appear on stage at big venues. A half stack is more common for medium-sized venues and recording studios—amp head on a 4×12. You should probably be asking if you need that. Do you need a 4×12? The answer here is also likely no unless the 4×12 delivers a sound that a 2×12 or 1×12 can not, or you need the slightly wider directional spread that a 4×12 has, but that is less common. Yes, the 4×12 sounds bigger, but often or not, the sound being chased after is a low-bottom-end growl that appears there but isn’t as present on a 2×12 or 1×12. They have a bottom end also, just not as much as the 4×12, which comes through more with it.

The 4×12 low-end growl appears because of some phasing (the speakers are in phase, but the proximity effect produces subtle phasing that changes the tone) between the closely arranged speakers in a 4×12 arrangement. This growl is less present in the 2×12 and 1×12 cabinets. Does this mean you need a 4×12 for growl? No. You can get growl from a 1×12, but the 4×12 has it in a way that the 2×12 and 1×12 don’t. The 1×12 will have a growl, but not the one that appears with this phasing. A 2×12 horizontal is better than a 2×12 vertical for the growl because the vertical has a baffle between the speakers. The horizontal 2×12 and the horizontal rows of 4×12 do not. The 4×12 is more pronounced with growls, and some players want that. Then, a 4×12 is the way to go.

A 2×12 or even a 1×12 is often sufficient to hit the tones you want to hear. Your neighbors can also hear them, for that matter. You can even have two 1×12 cabinets and a possible stack of 2x(1x12s) at home and change around your combinations. We have 2×12 cabinets around because higher wattage amps, especially 100W, are too powerful for some 1×12 speaker choices that guitarists like. So, a 2×12 is needed, or else damage to the equipment can occur. We shall talk more about how to calculate wattage loads like this shortly.

Combos are generally found in either 1×12 or 2×12 at the most. 2×12 combos can be heavy, as even a 1×12 can be hefty. Combos can be much heavier than they appear. If you intend to carry them, you must check them out or have a good idea of your weight and size. Getting this wrong has ended many combo and guitarist bonding attempts. Just too big to lug around. If that’s an issue, consider 1×12 at the most and maybe reconsider a combo for a small head and 1×12 you can carry separately back and forth to your vehicle. 1×10, if even that is too much.

These are options to save your back. Nothing is worse than being wasted before you even begin your set because you lugged around heavy gear and still have to lug it again afterward.

Speaker cabs can contain duplicates of the same speaker or a mix of speakers. Most cabinets allow for a speaker to be replaced. They are either front-loaded by removing the grill or rear-loaded by going in the back. Cabinets can be chained together; however, it is essential to understand impedance settings, or you can damage your amp and cab. We will talk about impedance soon.

The speaker is the last stage of a guitar rig. Your other gear and playing to create a sound that will only be as good as your speaker setup. However, microphones can help shape your tone through a mixing desk or DAW.

A 10” speaker isn’t going to cut through a crowd of screaming fans in an open arena. A full-stack (two 4x12s on top of each other) will blow eardrums in a small venue. They should be swapped around, and their problems would be sorted.

Professional guitar recording studios have a room that is kept soundproof and separate from the guitarist playing next to the mixing console most of the time, with the sound engineer telling them what they need. If the cab is in the same room, it may be behind soundproofing or in an isolation booth. In most cases, the rig will likely be loud, and the speaker pushes vast volumes of air out. Microphones are used on the speakers, right up against the fabric, back a bit, or placed around the room to add natural reverb to a mix.

Most guitarists will not have the luxury of such separation, but that full studio setup can play anything from a full-stack to a small 8” speaker in any setting they want.

Lugging around a 4×12 is no fun. They are heavy. Some people don’t mind. Most do. That will likely mean you, too. A 4×12 sitting in a spacious garage or basement might be more than the space needs, but it can work there and produce the tones sought from a 4×12. A home room should not need more than a 1×12, but a 2×12 might work in larger situations, like a big basement or attic. These are much easier to take around than a 4×12. In most cases, in a big attic or basement, a 4×12 is just way too much. Your ears should be telling you this. There is simply no reason to feel physically uncomfortable around your sound. The only people to suffer such belly rumbling are guitarists in big venues or fans who decide to get as close to the 4×12 speakers as possible. Studios have enclosed booths for them. Many guitarists opt for cab sims and or attenuation if the sound is too loud to coup with.

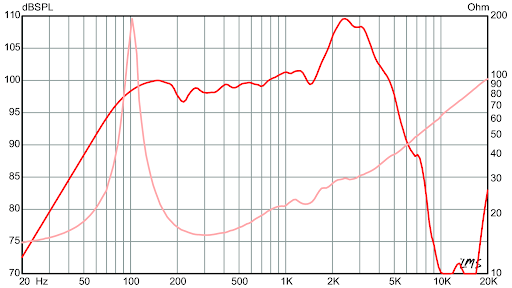

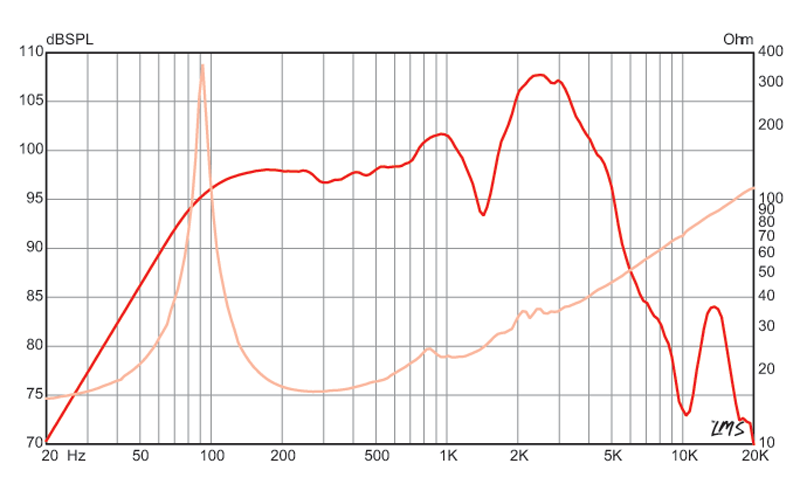

Guitar Speaker Frequency response

A way to read a graphical representation of what speakers sound like is to look at frequency response charts if they have one or dig it up from the internet. If you look at these charts, you will see this mid-range we keep discussing. These charts don’t tell the whole story, which means the cab they are in, the amp before them, and the environment play a big part in response. So, these charts are a rough guide for what to expect. The differences between charts are subtle response changes that can significantly affect your tone.

A speaker frequency response chart is initially daunting but easily explained. What better way of testing a speaker than running a signal through a range of low to low-mid, mid, high-mid, and high frequencies? Then, we report back how loud we need to get for each frequency to cut through. So you can read whether the frequencies respond or not. Depending on speaker designs, only some will get through. That is why speakers are almost synonymous with filters. You can get speakers with all sorts of variations in response, but guitar speakers will generally be mid-range focused.

Celestion V30 speaker frequency response.

Celestion G12M Greenback frequency response. Look from 200Hz to 8Khz for the mid-range area.

So, if you want more low-mids (called bass tentatively in this context), pick a speaker that responds well in the low-mid region. If you want less bass, you pick a speaker that is even less responsive there. It is the same with the high-mid region (called treble or high end somewhat tentatively in this context).

You can pick speakers that respond with low or high at the high end. However, bass and high-end aren’t that important to us. What is essential is the mid-range. Again, that concept of mid-ranges appears.

That hump is what cuts through in a mix. Are the low-mids low, medium, or high? Are the highs-mids low, medium, or high? These are the areas for you to think about first. Your speaker should be selected with these in mind.

Comparing frequency response curves, there is a temptation to look to the far right between 10kHz to 20kHz, where there seem to be many peaks and troughs like a stock market downturn. This range will tell you something about how the high-end response, 10kHz to 20kHz, is extreme, and only the highest-sounding notes, especially harmonics, register in this region.

What is far more interesting to us for the high-end are the frequencies between 1.5kHz and 10kHz. The range between 200Hz and 1.5kHz, that bump is really where the mid-range is all happening. That is what you should contrast between speaker frequency responses first of all. The larger pattern across the chart is nearly identical for all electric guitar speakers. Even this mid-range is somewhat similar. So is the high-end. It is the very subtle variations that make the difference.

You must hear them in context (different cab designs) and why these frequency response curves are only part of the picture. However, this is the objective way to measure speakers and engineer them to electric guitar tone standards.

See Eminence’s CV-75, Swamp Thang, and Texas heat speaker examples.

Eminence CV-75.

Eminence Swamp Thang

Eminence Texas Heat

The decibel scale is different, but the overall pattern is the same. Minor changes are happening in the middle ranges that matter to us.

A frequency response chart tells you a lot about electric guitar tone theory. 200Hz to 10kHz is that range of mids that blend slightly into bass and treble on the extremes.

An excellent way to experiment here is to open up some guitar track that isn’t distorted too much in your DAW. Then, add an EQ plugin and change the frequency ranges to resemble the pattern you looked up in the speaker frequency response. You should find some correlation between how the tones sound.