Chapter 2

The Power Stage

The Power Stage has nothing to do with standing on stage and having your big guitar moment. Well, it does, in a way, but we are talking about the technical concept of a guitar amplifier’s power stage. It may seem more logical to start with the amp at the pre-amp section and end our talk with the power stage, but understanding the power stage is more helpful in coming to terms with what the pre-amp section does for now. It will be a short section for a complicated topic, but there are many details to absorb.

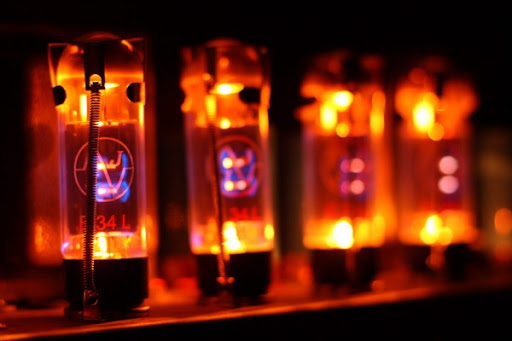

All you need to know is that the power stage is primarily responsible for the volume output your amp can achieve. It is not the only thing that can increase volume, but it is your amp’s main volume force. Previously you saw some large valves in an open amp. That is a power stage component.

Power tubes are usually never shielded.

The smaller valves, sometimes in shields, are a pre-amp component.

Shielded pre-amp tubes. They help reduce possible interference by locking in the tube with a spring on the top.

With solid-state systems, these components are transistors. So imagine no tubes means solid-state and even something more like a laptop circuit with high-end modelers and profilers that have computer processors onboard also performing computations to emulate an amp.

There are a few types of power tubes. Most amps are designed for only one type, but a few can use different types. You have to read the specifications and manual to learn more. EL34s, EL84s, 6L6, 6V6, KT88, KT66, and 5Y3 are the most common. There are many more. They all have specific tonal characteristics, although their differences can sometimes be quite subtle. For example, the KT66 and the 6L6 are almost identical. Anyway, subtle differences get amplified with amplifiers, and therein is some reason why engineers make a choice.

When a guitar signal passes through an amplifier’s power stage, the signal increases, and you hear the clean string plucking sound louder and processed by the amp. The increasing volume raises the clean sound until the tone changes when it breakups up and then changes again to heavy distortion and the heaviest when on maximum (cranked), which could sound very muddy (lacking any definition and coming across as one big block of sound). The clean sound will gradually be distorted with volume. A clean sound is gone when the volume goes beyond a certain threshold, and this breakup becomes distorted as the volume increases.

All distortions are different, so many high-gain amps, distortion pedals, and software distortion plugins are on the market. There are as many ways to distort as there are sounds to sculpt. Therefore each amplifier maker designs their amp so that the distortion from gain and volume increases creates a specific tone. That tone is part of the character of the amp’s inherent distortion and identity. You can’t get rid of it and have bought the amp because of it. Likewise, the amp will also have a clean identity before breaking up.

Power stage distortion

In theory, digital should be able to replicate everything. However, power stages, especially regarding valve systems, are highly reactive to increases in volume. So if there is any difference between the tone of a digital or solid-state guitar rig and the valve counterpart it is trying to copy, it often comes down to this power stage component.

The most expensive digital modeling/profiling amps appear to put a lot of effort into making their power stage sections react as a valve power stage will. That’s not to say cheaper modelers can’t do better. In general, achieving faithful reproduction of the power stage is essential because many electric guitarists will get the tone they want here. We are pointing out this correlation as early as possible to you for a reason. The reason is that when people are new to all this and engage a guitar amplifier, they will treat it like a Hi-Fi system where volume is just something you turn up to hear something and EQ to increase some frequencies for a few seconds showing off your bass sounds to your friends. Guitar amps are very different. Those dials are essential to achieving the tone through which a signal is put through. Hi-Fi systems are just faithfully replicating the media playing through them. You don’t want faithful replicating of string twang plucking with guitar amps. You want to sculpt that into an electric guitar tone with the amps properties.

The gain dial will almost certainly be the dial the user associates with distortion. The problem here is that volume also contributes, and depending on the amp, maybe considerably so. So while you almost surely will be dialing in distortion using the gain feature on distortion channels, you also need to know that volume can do it. Unfortunately, the correlation between tone and volume is not something we can express as a graph because every amp is different. The guitar you plug into them and its setup can change everything again.

A way to look at the dials on an amp is not that they can give you a wide variety of sounds but that it gives you many ways to get the channel’s tone. In a way, it can be considered a combination of an additive and subtractive system. Where your guitar tone lacks bass, the bass dial can give you more. Where your guitar tone excels in the mids, the dial can hold it there. Where your guitar has too much bite in the high end, we have trebles we can bring down. If these descriptions seem like we are putting the tonal goodness within an amp before the tone we want, you have already reached quite an understanding of guitar amplifiers that many never will. The right amp for the right tone is essentially everything. We don’t try to make an amp fit a tone. We get the best of what the amp offers and take it. You can not get blood from a stone. Supplementing with pedals is not the best choice for achieving tone if an amp can do it inherently. Go with the amp. Don’t waste money on a pedal platform that will give you a taste of the real deal, which may cost a few hundred or a thousand more to get there. You will only spend more and sell off the prior system at a loss. This differs from never using a pedal platform or not using pedals. This is about getting the foundation tone before building upon it. That means the amp.

A lot of 80s metal was achieved by cranking the volume of a highly power-stage reactive amp. Of course, you will not tolerate that in a home, but that tone is what some want. So the question becomes, how do I get loud volumes at low volumes?

Recorded loud but quieter playback

If you listen to guitar on songs and the tone is achieved at loud volumes, sounding big or thick, you don’t have to have your Hi-Fi also at ultra-loud volumes to hear it. Instead, you can hear it at lower volumes (and yes, even HiFi volume does change tonal characteristics to some degree). Take a CD or MP3, for example. The tonal character you want is found there digitally.

The digital realm of recreating guitar tones has long ago understood that if they can simulate a cranked amp, there is no reason you can’t turn down the overall computer sound monitor volume. So the computer and software are processing the tone as if it is the tone achieved with a simulated amp set very loud amp, but you can play that tone back at lower volumes or even hear it live at lower volumes.

The volume levels that distort tone are within the system, and you turn up your monitoring speakers to hear it like you would listen to it from an album on a HiFi system. In theory, this is beautiful and exactly what high-end profiling and modeling gear seem to do. However, the problem here appears to be the same one we discussed. Power stage replication is complex. While some profiles on modeling systems have achieved near-identical sounds to a tube amp counterpart, other profiles may not be as good. It is also not uncommon for profilers to go through an additional power stage unit to increase volume output again, especially at venues for performance.

You are probably asking, why not just go fully digital, then? To cut a long story short, through experimenting, engineers have found a way for modern guitarists to do this in small environments, harnessing any amp they want using attenuation systems, especially a loadbox. These units are usually in addition to the amp and are bought separately. However, more amps come with inbuilt attenuation and power staging switching from 50W to 20W to 5W in one amp.

Some amps have power staging to switch between wattage modes. This Marshall Studio Jubilee has low 5W mode or 20W full power mode.